When remasters of Heretic and Hexen were surprise-released last week, my interest was piqued despite myself. I played both in the ’90s and didn’t love either of them. Released in 1994 by Raven Software, Heretic was a fantasy take on Doom and it was OK. The following year Hexen offered an RPG take on Doom—by way of Heretic—and it drove me nuts.

The weapons in Heretic were novel enough. I loved the shotgun-adjacent ethereal crossbow a lot, and punching gargoyles in the face with magic bracers was weirdly funny. It was always kinda cool how you could collect items to use later: spamming a hall with a dozen Time Bombs of the Ancients and watching swathes of golems perish felt pretty clever compared to just pointing and shooting at them. But overall the game wasn’t different enough from Doom to excite me. Its approach to fantasy was pretty cartoonish, especially compared to what would come later in the form of Hexen.

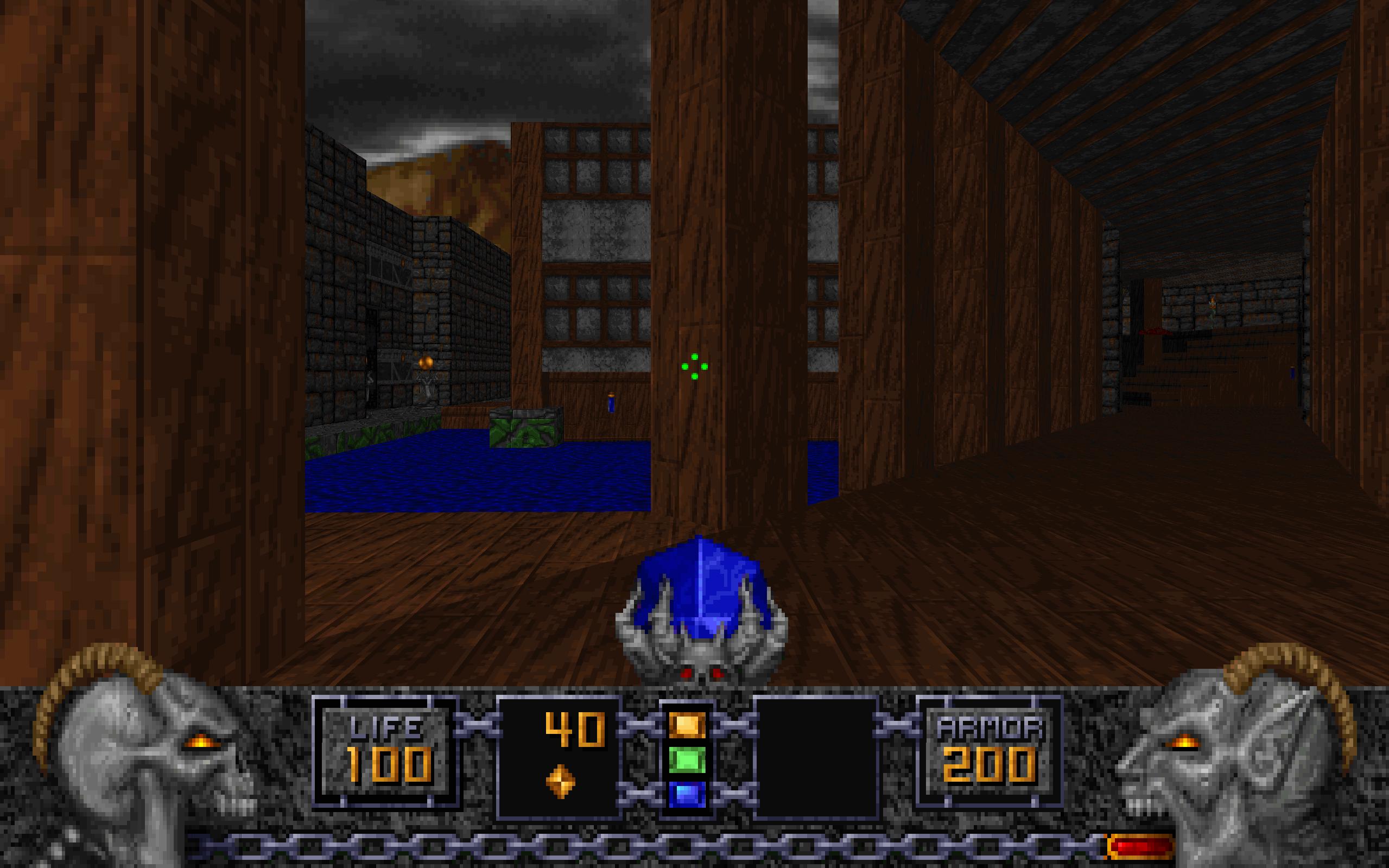

But playing Heretic in 2025, it’s much better than I remember. This might have to do with Nightdive Studios’ brilliant handling of the remasters. Whereas the engine powering Doom and Heretic capped out at 35 fps, you can play these new remasters at 120 fps without using a source port. Widescreen support and crisper graphics definitely helps too, as does an almost supernaturally smooth free look (you could look up and down in the original Heretic, but it was super awkward, and there was no good reason to do it). It definitely feels like an indie boomer shooter now, with that ’90s sense of indomitable speed. Unlike say, Rise of the Triad, it has aged remarkably well.

Watch On

Nightdive has also made gameplay tweaks, some of which—honestly, most of which—you probably won’t notice if it’s been a quarter of a century since you last played these games. Some maps have been tweaked in both Heretic and Hexen, mostly to make them more parseable and less cryptic, and some weapons have been very subtly changed. The ammo capacity of the ethereal crossbow has been decreased, for example, meaning you can’t just main it. You can toggle these changes on and off.

But I also think there’s another factor that makes me appreciate Heretic more in 2025 than I did in 1994: it’s the level design. Heretic’s world makes a whole lot more sense, and is a whole lot more sophisticated on an architectural level, than the level design in Doom.

Heretic originally arrived only a matter of weeks after Doom 2’s October 1994 release date, but it still manages to better the level design even in that sequel. In fact, Heretic’s admirable attempts at creating real-feeling areas—see highlights like E1M4 ‘The Guard Tower’, and E1M5 ‘The Citadel’— feel like evolutions of Doom 2 highlights like ‘Suburbs’ and ‘Tenements’, despite being slightly earlier than them. All of these maps tried to simulate a sense of wandering through a hamlet, or a city, full of multi-storey tenements and warehouses, in an engine that couldn’t easily pull that off. Heretic’s approach felt more true to life.

Heretic is also really good at simulating a wide natural environment in an engine that’s much better suited to making hallways and dungeons. My favourite example is E3M3 ‘The Confluence’, which doesn’t so much try to create a lifelike river convergence as it does capture a dramatic high fantasy approach to one. Oh, and Raven’s early masterpiece has to be E1M6 ‘The Cathedral’, which is among the most colourful and atmospheric Doom engine levels I’ve played, but with a tomb-like approach to exploration that makes me feel like Indiana Jones.

Heretic did end up getting a proper sequel in 1998, but before that we got Hexen: Beyond Heretic in 1995. Though it’s also built in the OG Doom engine, Hexen is no retread of Heretic: it offers up three classes—fighter, cleric and mage—and four weapons for each. Some enemies carry over from Heretic, but the vast majority do not. It’s a big, blustering, ambitious attempt to make something akin to an action RPG—or maybe even something like Ultima Underworld: The Stygian Abyss—in an engine that’s all about fragging and finding keys. Raven obviously wanted to create a sprawling epic, and it got at least part of that ambition right.

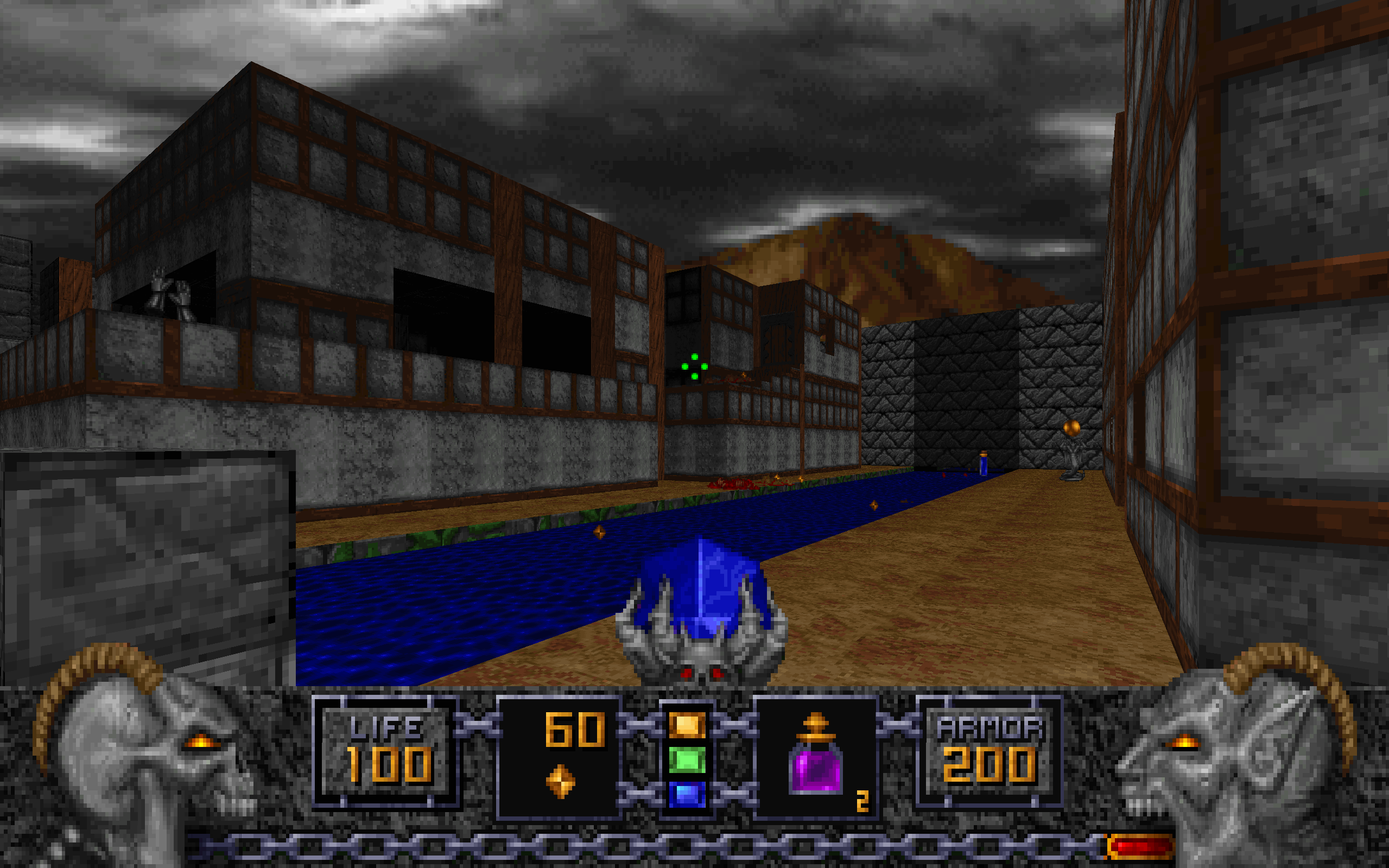

Nightdive has made some small but important alterations that serve to make Hexen… almost fun to play.

Because jeez does Hexen sprawl. Its biggest diversion from other Doom-engine games is its hub-based level structure. Levels branching from a hub generally hold the key—or a switch—that would open a new route in the main area. It was a cool idea (and this late in the Doom engine’s commercial life, Hexen needed at least one cool idea) but it resulted in a horribly obtuse outing. A supernatural reserve of patience was required in a game that often planted switches at the whole other end of the world from the door it opened. Even in the ’90s, when the novelty of exploring 3D worlds was still a huge part of the appeal of first-person games, it was an extremely rough trot.

To Nightdive’s eternal credit, the studio has done its best to make Hexen suck a whole lot less. You basically always needed to use the map in Hexen, but now the map is heaps more useful, showing the location of important switches and doors even if you haven’t visited the location yet. In addition to that, the hub areas now have little signs in the environment that provide a bit more clarity regarding what you’ve done so far, and what still needs to happen. You can even change your class mid-game, now.

Nightdive could have just re-released Hexen with some cosmetic improvements and left it at that, but instead they’ve made some small but important alterations that serve to make Hexen… almost fun to play. The truth is that the hub-and-spoke design tends to result in some very dull, very perfunctory-feeling spokes, most of which can’t hold a torch to the gorgeous level design found in Heretic.

Though I never loved either of these games in the ’90s, I reckon Heretic + Hexen is a brilliant package. Heretic benefits greatly from a cosmetic uplift, and the Nightdive-created levels make it attractive for players who remember the original more vividly. Hexen is a curio, but hell, it sure has a glorious mood, and it’s fun to see all the different ways studios were scrambling to squeeze blood out of the Doom engine (see also: Strife). This is a more ambitious archival project from Nightdive than the recent Doom treatment, for its focus not just on posterity but modern playability.

Read the full article here