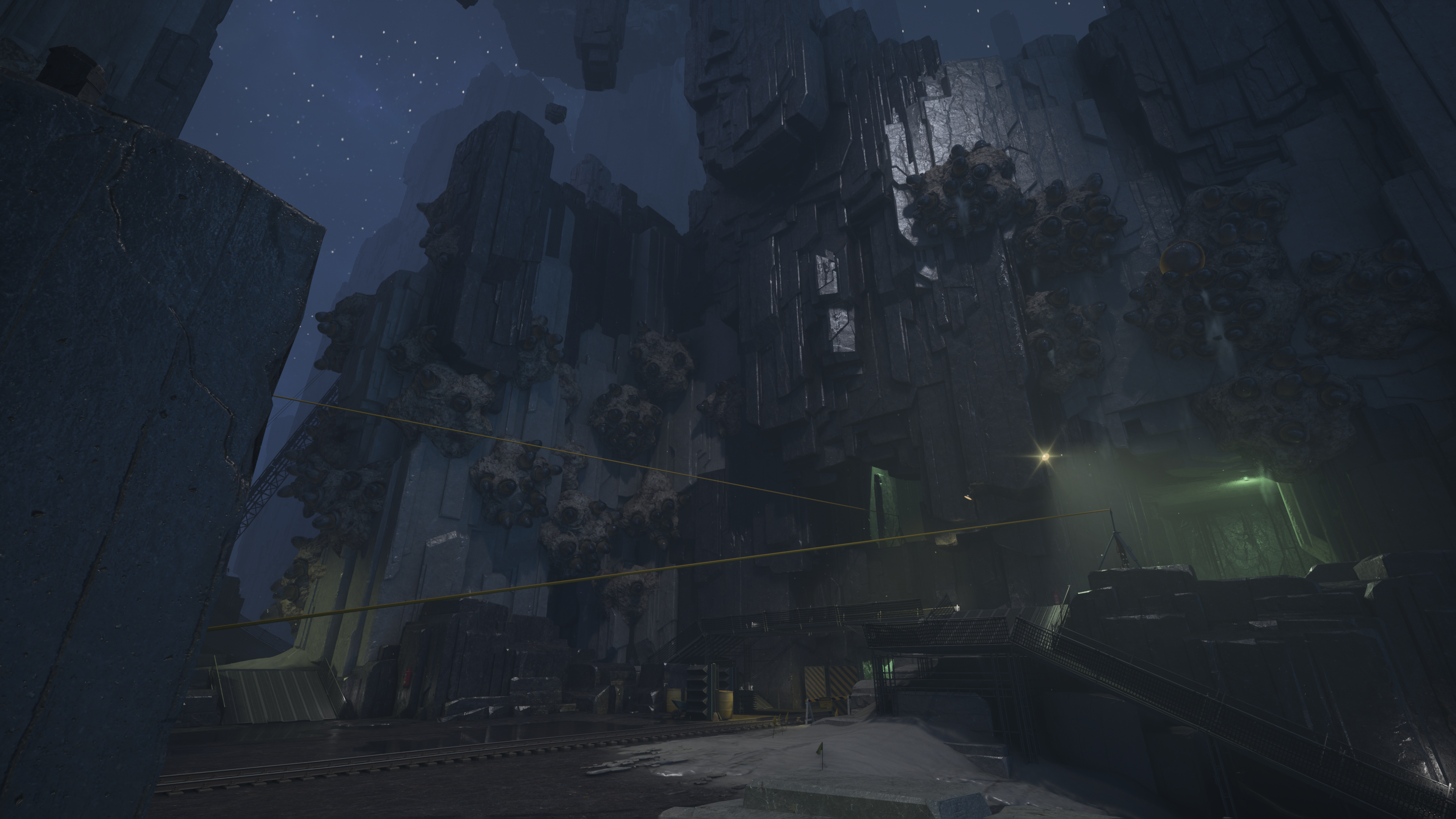

Though it takes place in the same setting as Control, it could not be any clearer in Remedy’s new co-op shooter that you are no Jesse Faden.

Forget telekinetic superpowers and shape-shifting weaponry—this time you’re just an expendable grunt, sent out to do jobs so dangerous that your objectives are more likely to kill you than the hordes of Hiss-possessed ghouls.

During my two-and-a-half-hour hands-on with FBC: Firebreak, I truly never knew what to expect as I jumped into each new mission—though “something unpleasant” was a good rule of thumb. One minute I was transporting deadly radioactive material in a nightmarish quarry full of giant leeches, the next I was desperately dodging through an office trying to avoid being engulfed by parasitic post-it notes.

They build these devices, or they’re using a paranatural object, that is probably a little bit too powerful for their own good.

Anssi Hyytiainen, Lead Designer

Even mid-mission I often found myself blind-sided by some new lethal wrinkle in the plan. An excursion to repair malfunctioning furnace fans that keep intermittently spewing flame already felt risky enough—my team and I couldn’t quite believe it when our objective marker indicated the next step was to finish the repairs by crawling inside them and hammering away while literally on fire.

“Definitely a big reference game would be the way that friendly fire, for example, works in Helldivers 2,” says lead designer Anssi Hyytiainen. Certainly the travails of our team do evoke some of Helldivers’ slapstick comedy and satire. We’re redshirts, not heroes, messing with forces beyond our control. “They build these devices, or they’re using a paranatural object, that is probably a little bit too powerful for their own good.”

Back to work

But you’re not just there to die and laugh at each other’s misfortune—you’ve got a job to do. The lethality of the objectives forces creative teamwork, using the game’s suite of strange tools and systems.

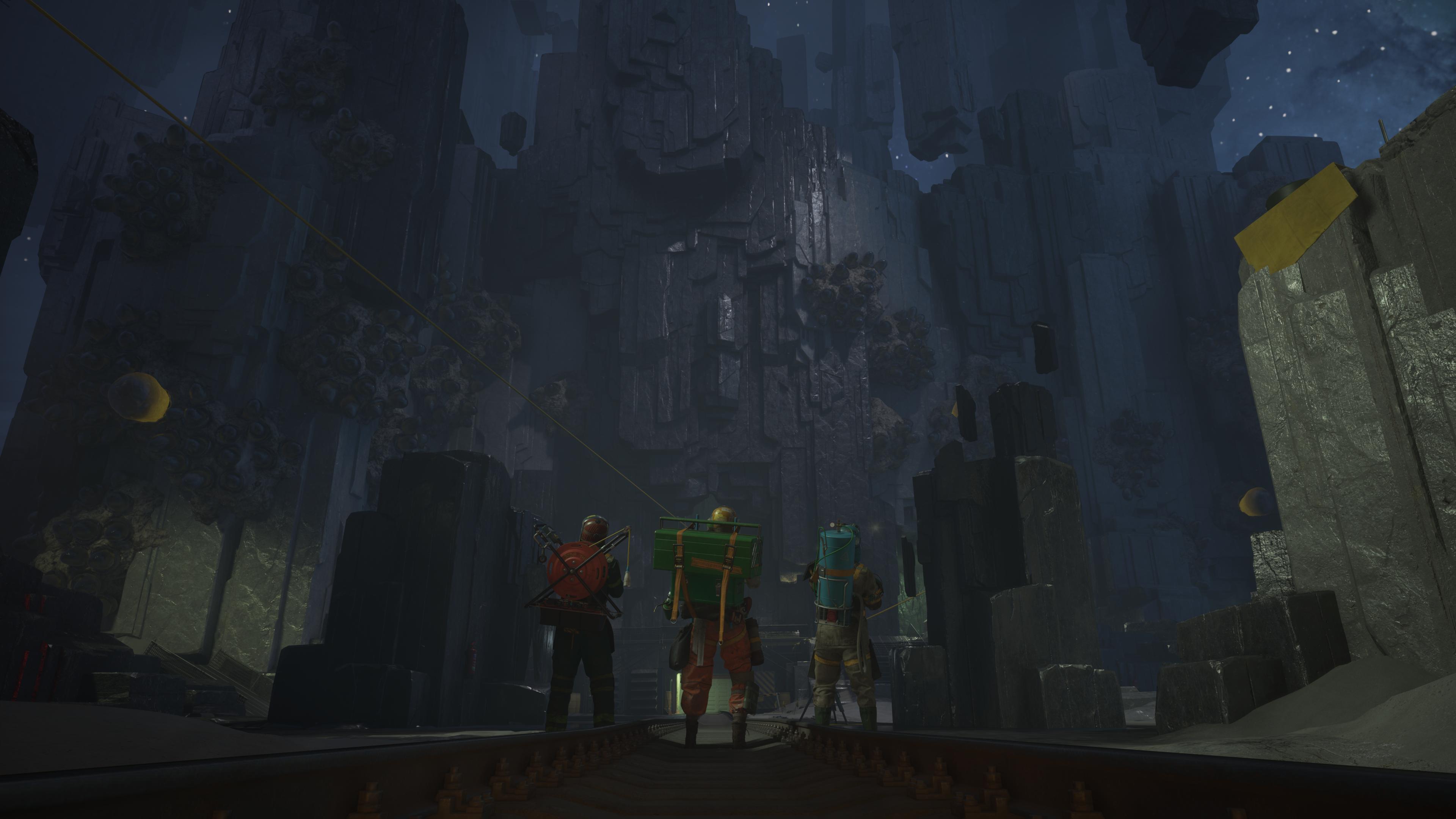

Instead of classes, each player is defined by their “kit”. The fix kit allows you to be a sort of close-range engineer, while the splash kit makes you a water-spraying support, and the jump kit lets you both jump (up to high places) and jump (-start electrical devices). Each has its own combat applications, but in a manner reminiscent of Deep Rock Galactic, they come alive in how they combine to solve practical problems.

While I’m bashing away with my wrench in a rapidly overheating fan tunnel, my buddy can be spraying me down with water to keep the flames at bay.

While I’m bashing away with my wrench in a rapidly overheating fan tunnel, my buddy can be spraying me down with water to keep the flames at bay. Next mission, he’s soaking piles of living post-its instead, ready for our jump-kitter to zap them with a charge of electricity, while I set up a sentry gun to cover our imminent extraction.

Figuring out your plan and putting it in motion is made more tense and tricky by hordes of Hiss constantly bearing down on you. When you’re not frantically hauling something dangerous or trying to fix something in a panic, you’re probably firing a shotgun or an SMG into the masses. Though with a pretty standard selection of weapons outside of your kit, and gunplay that’s robust but not necessarily thrilling, the waves of enemies don’t feel like the main focus, despite their often overwhelming numbers.

They do demand some tactical thinking—rushing into the mob to take out a key target, or distracting a larger foe so an ally can loop round to hit the weak spot in its back. But despite their creative visuals (they’re mostly ported over directly from Control’s weird menagerie of possessed office workers and security staff, but look even more striking bearing down on you in first-person), they largely amount to a familiar zombie horde.

That makes them more an environmental pressure than an organised foe. They’re there to push you to sprint for that next ammo station, speed up your repairs on the decontamination shower, make a break for the extraction point, or get quick and sloppy with a dangerous objective.

And the same systemic interactions used to overcome the obstacles in your path can be thrown their way too. Whacking them with my wrench certainly got a lot easier once they’d been drenched in water and then shocked first, while fire proves a double-edged sword against them. Heat from nearby fires speeds them up, making them more dangerous, but if they get too hot, they’ll combust and perish just like your team.

Each kit allows you to push that further with an augment—essentially an ultimate ability that you can deploy to ramp up the chaos to even more agreeable levels. From firing globules of scalding hot tea, to deploying a lightning storm gnome, to strapping an explosive piggybank to your melee weapon, they’re a fun injection of distinctly Remedy strangeness into the action.

Overall, though I have enjoyed my time with the game so far, I’m not sure there’s as much depth here as I’d like. Combat does the job, but there doesn’t seem to be as much to get to grips with or discover here as there is in genre-mates like Darktide or the aforementioned Helldivers 2.

And with only three kits and relatively limited customisability, it does feel like a few too many of the objectives and environmental obstacles that make up the meat of the experience can be resolved with fairly similar ‘water + fire/electricity’ solutions—it’s not as varied a test of your creative thinking as Deep Rock Galactic, even if the situations are often stranger.

But it does all combine to create that lovely feeling that you’re actually working together to achieve something, rather than simply carving through waves of foes, with plenty of visual novelty to each task. And such systems-driven action is certainly a fascinating departure for a studio known more for meticulously-crafted storytelling, scripted sequences, and elaborate musical numbers.

Altered world

“PvE kind of screams ‘this needs to be more of a playground type of experience’,” says Hyytiainen.

“We want this game to be something that you can play multiple times,” adds lead level designer Teemu Huhtiniemi. “The whole idea is that you can just jump in and have fun. And of course, when you’re making an experience like that, you need to make sure that it’s fun to play like, 100 times, and you always get something a little bit different.

“I think a lot of the appeal of the project, in-house, also comes from the fact that it is so different from what we’ve done before … it was an interesting challenge to see, okay, how do we do this?”

It’s a change of scene for Remedy in more than just the shift in genre. Though the development team includes long-standing veterans (Hyytiainen, for example, has been at the studio for 25 years) it’s a small project compared to the main team working on Control 2, and for the first time in Remedy’s history, it’s completely self-published.

That makes it an interesting experiment. Now that the studio has established a connected universe for its games, can it expand it further with smaller spin-offs, rather than only with big, expensive mainline entries? And can that setting support games outside of the singleplayer third-person action genre?

As a huge fan of Remedy, I’d love to see this open up new possibilities for the studio—and I certainly think there’s enough of the creative design and unique atmosphere of Control in FBC: Firebreak, despite the lack of more traditional storytelling.

Office politics

What my time with the game doesn’t reveal is where in the crowded co-op space this game really fits, however. Though it has plenty of challenge—with multiple different ways of tweaking the game’s difficulty and how long and intense you want your session to be—it’s by design a casual approach to online multiplayer, not demanding the investment of time of a full live service game.

There’s definitely an appeal to a co-op game in 2025 that doesn’t ask you to swear your life to it, but I do worry that approach will make FBC: Firebreak easy to pass on. The same quirky concepts that make it intriguing also make it fairly niche, and probably most appealing to Remedy’s core audience, who aren’t necessarily looking for a multiplayer experience. Combine that with what seems to be a pretty modest offering of content and relatively limited strategic depth, and not only does finding an audience seem far from guaranteed, I question how long the players it does reach are going to stick around.

It just opens up a world of possibilities, creatively, for what we could do.

Teemu Huhtiniemi, Lead Level Designer

But perhaps that’s worrying over-much about the studio’s bottom line. What should probably matter more to you, if you are a Remedy fan, is that this does feel like a worthy extension of this strange and fascinating world that’s been unfurling in Control and Alan Wake 2. There may not be FMV cutscenes, audilogs, or an entire Finnish horror movie hidden anywhere in FBC: Firebreak, but what it does offer is a wholly new perspective on one of gaming’s most unique settings.

“We were thinking about the Oldest House and how weird it is, and the concept of experiencing it through the eyes of a normal person,” says Huhtiniemi. “Someone who doesn’t have the superpowers, and someone who needs to overcome impossible odds. That felt really exciting as a thought already … having that perspective alone, it just opens up a world of possibilities, creatively, for what we could do.”

To Jesse Faden, the Oldest House is a playground for telekinetic action. For the “volunteers” of FBC: Firebreak, it’s a vast and hostile prison to outfight and outthink together—before you accidentally fall into a giant furnace, die of radiation sickness, or get turned into a post-it note zombie, and the next guy in line steps up to take your place.

You’ll be able to step into that meatgrinder yourself when the game launches on June 17 later this year.

Read the full article here