Isn’t it a bit messed up that we selectively breed cats and dogs into asthmatic oddballs and then sell them to each other? I love cats, but, yeah, it is a bit messed up. That’s basically what inspired Mewgenics, a game about breeding cats and sending them on adventures with turn-based combat. (So they’re outdoor cats.)

The idea for Mewgenics has been around for a long time: It was once going to be Team Meat’s follow-up to 2010’s Super Meat Boy, but was shelved and designer Edmund McMillen went on to make hit roguelike The Binding of Isaac. He never lost interest in the cat game, though, and has now been working on it with frequent collaborator Tyler Glaiel for years.

They’ve ended up with something huge—200 hours huge, they say—and comically grotesque in all the ways you expect from McMillen, whose provocative games fixate on things like mutilation, disease, and decay. The title alone may raise some eyebrows with its play on “eugenics.” McMillen thinks it’s his best game yet.

Cat tactics

To pull one of PC Gamer’s favorite terms out of the bag, Mewgenics is systems-driven to its core, with so many abilities, traits, items, enemy behaviors, hazards, and other effects at play that when I sat down at McMillen’s desk to try it recently, I was rarely certain about what exactly would happen when I clicked something.

Mewgenics is systems-driven to its core.

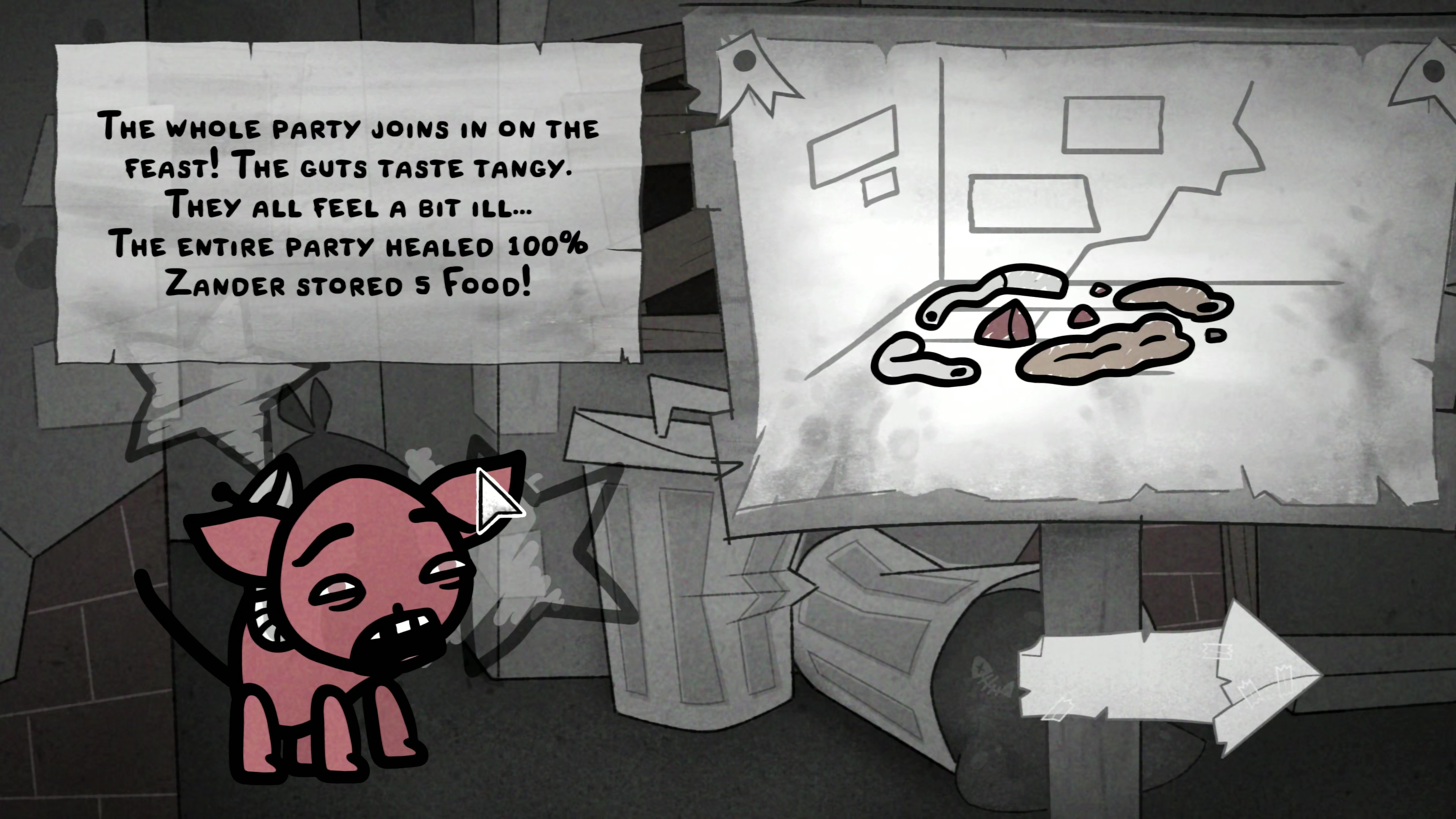

If you were helping someone learn to navigate Mewgenics’ tactical cat battles, you’d be saying things like, “Well, that ability will blow that enemy over there and then he’ll get harpooned on the next round, which’ll make him bleed so that shark will attack him, but watch out because you’ll also blow that fire onto one of your cats” and “If you use his charge attack he’ll end up in the tall grass, which is good, unless there’s a bear trap in there that you forgot about.”

When I kept summoning a hitman who straight up shoots enemies (because of course I wanted to spam that ability), McMillen pointed out that I was spending money every time I did it, and so might not be able to buy anything when I got to the store.

The adventuring part of Mewgenics sees you navigate chains of battles, events, and boss fights as in games like FTL and Slay the Spire, and so battles involve meta considerations about the whole run, as well as your overall strategy for the whole game, which’ll take multiple excursions to complete and also involves renovating your home and managing your cat legion.

Unintended consequences

The theorycrafting seems primed to get out of hand the moment Mewgenics is released to the public.

As I repeatedly sent my cats careening into the deadly consequences of my decisions (they were on fire quite a bit more than cats like to be), I took some comfort in knowing that the designers themselves are frequently undermined by the unintended consequences of their ambition.

As one example, they made a certain enemy spawn frogs to represent pestilence, and flies to represent famine, but forgot that the frogs would use their first turn to eat all the flies, because frogs eat flies. Well, what can you do? Frogs eat flies.

The pair generally doesn’t get rid of funny or overpowered interactions, unless they soft lock the game or really screw up a fight. In one instance, a bomb-throwing boss was completely thwarted by rain, which instantly extinguished the fuses on the bombs. They did change the boss’ behavior in that instance, but didn’t stop rain from extinguishing fuses, because it just should.

The theorycrafting seems primed to get out of hand the moment Mewgenics is released to the public next year. Cat abilities and spells come in multiple class flavors—fighter, necromancer, tank, etc—and the designers are confident they understand how all the abilities within a class work together (each has 50 actives and 25 passives), but players are going to mix-and-match. They’re sure to find unexpected ways to stack status effects like poison and exploit environmental hazards.

I kept using a certain basic ability just for the heck of it, because it seemed delightfully useless: “Look At Me!” makes all of the enemies turn to face the cat that used it. But backstabbing is an automatic crit, so I figure there has to be some way to make tactical use of the ability. Mewgenics seems like the kind of game where a hypothesis like that could become a multi-evening fixation.

Difficult terrain

In the time since he had the idea for Mewgenics, McMillen has become a father and has realized that it isn’t just about cat breeding, but also “having kids, and legacy, and passing down genetic traits, and praying that whatever foundation you left there will be used in the future.”

When you aren’t directing cat battles in the field, you’ll be caring for your feline adventuring parties at home, decorating and renovating your house to suit their needs.

In a twist on the design of games like XCOM and Darkest Dungeon, cats can only be sent on one excursion before they retire from adventuring for good. That doesn’t mean they’re no longer needed, though: Your retired cats will defend your house from special bosses that show up as the story progresses, and most importantly, produce future generations of cat heroes. (Adoptable strays will also show up regularly.)

Kittens born to your amorous cats receive attacks, spells, and attributes from their parents, as well as disorders, including human ones like autism. That pushes Mewgenics into far riskier subjects than cat breeding: the personal decisions of individuals and couples regarding their genetics and children, and the concept of actual—not “mew”—eugenics.

Confronting players with uncomfortable subjects in an irreverent way is McMillen’s MO—The Binding of Isaac investigates religion by way of child abuse in a roguelike shooter where your bullets are tears—but he doesn’t do it without reason or reflection.

In Mewgenics, disorders aren’t debuffs. A cat with autism isn’t great at everything, but is very good at casting spells they’re born with. McMillen himself has dyslexia, and the disorder has a clever effect in Mewgenics, swapping sixes/nines and fives/threes in damage numbers and ability costs—powerful if you’re clever with it.

And that’s what this game is about: It’s about making it work, what you’re given.

Edmund McMillen

A very rare disorder in Mewgenics is primordial dwarfism, which results in a “teeny, teeny, teeny, tiny cat that has very reduced stats”—except for luck, which is through the roof.

“So you got, like, the luckiest fucking cat imaginable, like off the charts lucky, and you can abuse the fuck out of that,” McMillen told me. “You can make that work for you in amazing, amazing ways. And we try to do that as much as possible, because I like the idea of somebody viewing something as a downside and just seeing the downside, but then being like, ‘Wait a minute, I can make this work.’ And then they make it work. And that’s what this game is about: It’s about making it work, what you’re given. You’ve been given this hand, make it work.”

McMillen has been thinking about how to represent ADHD, which is also in his family, and says fans have been excitedly pitching ideas for how to include their own disorders. They like the challenge of representing their minds and bodies with game logic, and the idea that they might in some small way be understood through the context of tactical cat battles.

200 hours

McMillen and Glaiel know that they aren’t for everyone. Mewgenics projects a ’90s kind of edginess that revels in the world’s flaws: grime, disease, decay, senseless violence, and general stupidity. It’s the stuff I grew up with as a teenage fan of Newgrounds games and Jhonen Vasquez comics like Johnny The Homicidal Maniac, but McMillen hears the occasional onlooker wondering why his art is so “ugly” and questioning whether it’s OK for the title to reference eugenics.

“It’s not like the game is saying it’s a good thing,” he says to that. “It is very much not a pro-eugenics game,” adds Glaiel. The pair didn’t want to spoil anything, but say that their intentions will become clearer as we get deeper into its story.

I was surprised to hear how long that’s expected to take us: Glaiel thinks he could speedrun Mewgenics in 50 hours, but expects a first-time player to put 200 hours into it before rolling credits. They told me about the existence of advanced techniques like intentionally preventing some cats from leveling up in order to over-level other cats, something a casual player might not even notice on their first playthrough.

As for the art, McMillen and Glaiel are still using Flash for its distinctive style of vector animation. The bold lines and bulbous characters McMillen favors can make the battle maps hard to read, but I also saw a cool-ass boss animation at one point that surprised me with its slickness.

None have escaped the software-as-a-service era, even Flash game developers.

The software is actually called Adobe Animate now, since the Flash browser plugin is long gone, and Glaiel is peeved that they have to pay Adobe a monthly fee for the privilege to use it. None have escaped the software-as-a-service era, even Flash game developers.

The world may have changed since McMillen was making Flash games like Clubby the Seal, but Mewgenics’ sense of humor fits right into that oeuvre: It’s the only game I can recall playing that includes cat sex animations. And yet I came away feeling that he and Glaiel have matured as artists.

After a very small and fun sample of what’s apparently a 200-hour game, I’m inclined to trust McMillen’s judgment when he says that Mewgenics is his best yet. It’ll finally be out February 10, 2026 on Steam.

Read the full article here