As the shroom-hopping race begins, the starter’s pistol backfires, delivering a bullet straight through his foot. He hoots and curses, and the racers stall in the blocks, waiting for confirmation that the contest has really begun. I take the opportunity to grab an early lead, sprinting ahead into a field of oversized fungi. “It was a public service,” Fallen London’s silent narrator assures me. “One official’s podiatric misfortune can’t be allowed to disrupt the entertainment of the masses. He knew the risks.”

At one point, as a Turkish girl draws alongside me in the race, I’m given the option to let her by—the start of a potential acquaintance, perhaps? But instead I bound between spongy umbrellas and step over the opposition to take first place at the podium. “Someone complains when you step on their face to spring into the lead,” says the narrator. “Their diction was terrible. If they expect you to listen they’re going to have to enunciate.”

I return to the streets of London with a clutch of moon-pearls, glim and rostygold. But my winnings are just the highlight of a day in which I get my nose bloodied trying to save a bunch of urchins from gangsters, track a dirigible across the cavern sky to see whether it’s installing artificial stars, and travel to a tourist city in my dreams. Life in Fallen London is heady, breathless, and more varied than in any other videogame I could think to mention.

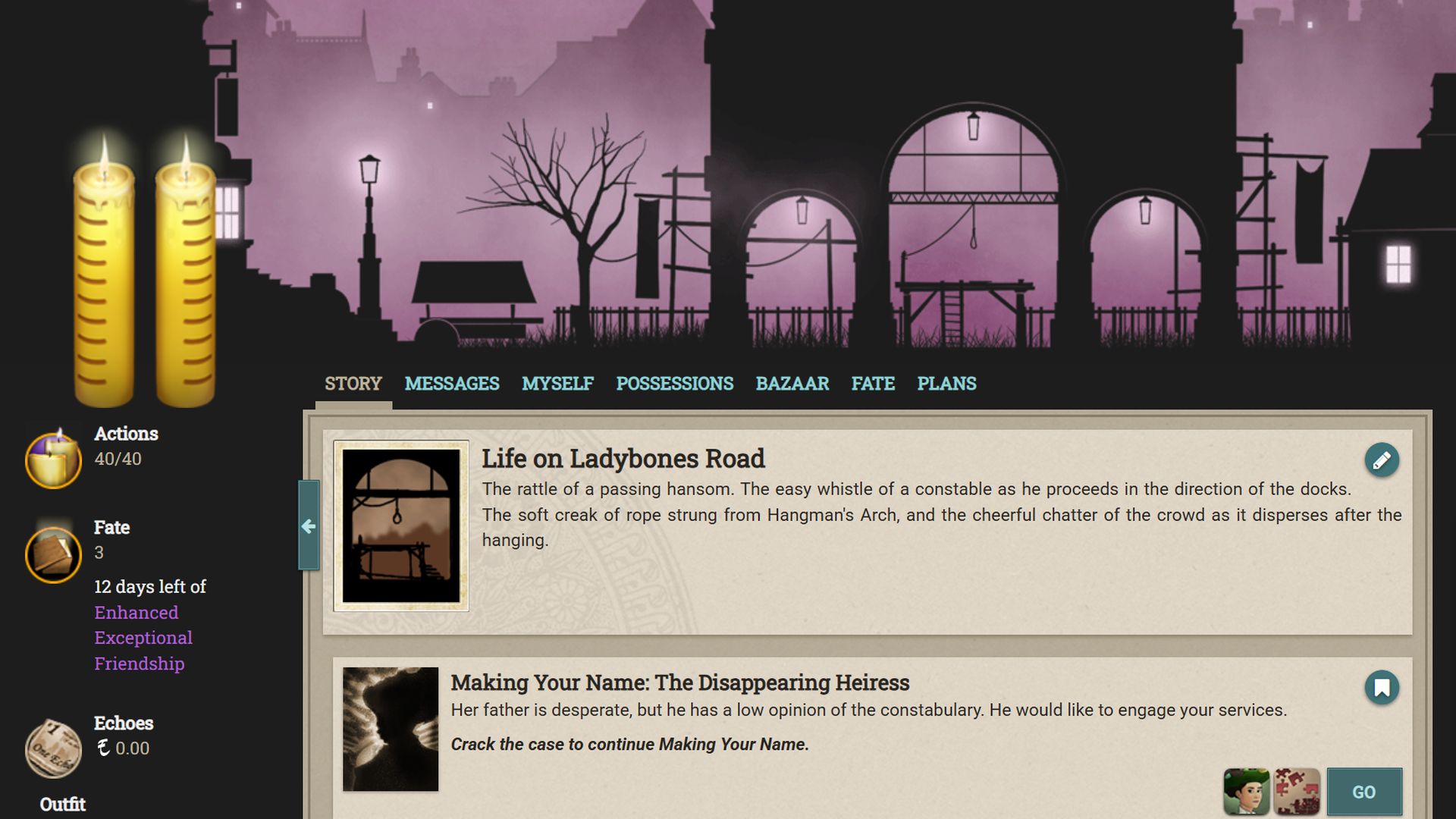

It is this way because Fallen London is a browser game almost entirely composed of text. Those who know about these things refer to it as interactive fiction. It’s not a visual novel, because there are no visuals, aside from the city map and thumbnail images which pop up beside each new paragraph of prose. Even the term ‘novel’ seems reductive, somehow, when applied to a game that’s home to around 4.5 million words and thousands of short stories.

Here’s an entire world conjured through eloquent, funny, frightening and idiosyncratic typing. One in which, at regular intervals, you’ll be asked to roll for RPG skill checks—learning how to become more Dangerous or Persuasive while you battle with rats for the rights to your fridge, or get to know the dandies of Veilgarden.

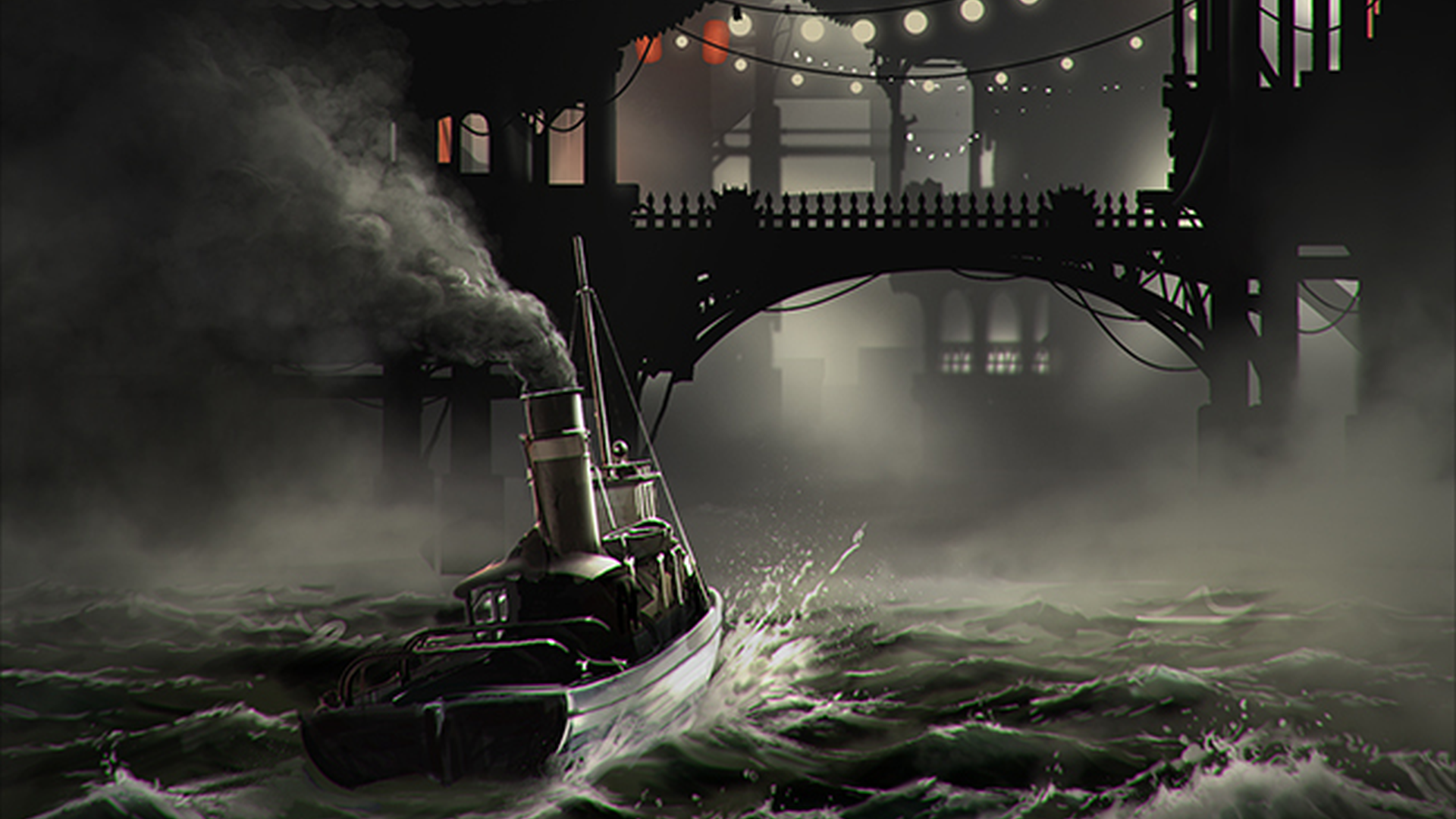

As a newcomer you break out of prison, Elder Scrolls style, and take up lodgings somewhere in the sunken British capital. I’m currently occupying a disused steamer on the shore of the Unterzee. It’s cold and a little lopsided, but allows me to pull an extra opportunity card out of the deck that throws up random events in London.

At least, they appear random at first. Before too long, you start to notice lingering threads. Sticking up for the urchins led to vengefully beating up a Baronet while his britches were down—and an ominous warning that “this might not be entirely over”. Sometimes old faces appear from the surface world, too, prompting questions about your background and purpose. What initially feels like a succession of disconnected scenarios eventually starts to mould you like clay—although the simile might be offensive, given that the Neath is also home to plenty of Clay Men.

Last week, I visited the home of the Clay Men, across the zee. It was one of the occasions in which I felt excited to slip under the gates of Fallen London’s progression systems and see something I wasn’t quite prepared for. After trailing a zailor down to the Wolfstack Docks—usually off-limits to new players—I paid my way onto a steamer to distant Polythreme.

Once on dry land, I found myself more asea than ever—completely lost in a culture I couldn’t make sense of, where clothes became sentient and buildings watched with benevolent eyes. Fallen London accounted for this discombobulation quite brilliantly; each time I set out to ‘promenade’, a dwindling resource offered a set amount of time in which to get my bearings. By exploring Polytheme’s markets and temples, I could gain Allure and Cognisance to spend on encounters with the Clay Men, observing their ways and speaking their strange all-caps language.

This new and bizarre system might sound baffling, and to begin with it was. But after several failed promenades, I came away with a genuine understanding of how the Clay Men lived, and the inherent sadness of their existence apart from the brick and mortar of the buildings around them. No other game, in my experience, has quite so precisely evoked the giddy unease of being a stranger in a foreign land.

Fallen London has many ways to adapt its mechanics to the peculiarities of the situation at hand—whether that’s shroom-hopping or confronting drownies at zee. But perhaps its best trait is knowing when not to lean on mechanics at all, and to let the prose do the talking. Most often, this game behaves like a light-touch dungeon master—one who isn’t a stickler for damage rolls, and is happy to let the rules go so long as everyone’s swept along by the story. Videogame RPGs have always struggled to simulate the breadth of options available at the tabletop—but by foregoing graphics, Fallen London circumvents the issue entirely. It can go to the depths of the ocean and the tallest spires. And I’ve been to both, in its company.

In one sense, Fallen London is a hangover—birthed as Echo Bazaar during the golden age of browser games a decade and a half ago. It more closely resembles the text adventure games of the ’80s than most of the PC games you might encounter on Steam. Yet it’s also a model for how to do live-service singleplayer, at a time when many big-budget publishers would love to wrap their heads around that concept.

Fallen London’s two subscription tiers double your cap of actions-per-day and bring new monthly stories—basically choose-your-own novellas which offer the moral choice paralysis of classic BioWare. And high-level players speak of building a railway to hell, an epic undertaking that constitutes an extraordinary endgame, whether you’re paying or not. As far as I can tell, developer Failbetter has accelerated the pace of updates, even while concurrently developing other games, like Mask of the Rose and the upcoming eldritch farming sim Mandrake.

As for the future? All I can tell you is that I’ve deactivated my Fallout 76 sub for a bit, and can’t wait to see where Failbetter’s dirigibles take me in the meantime. Fallen London may not have graphics, a physics engine or any sound, but those deficiencies are also its superpower. This slimline fantasy world will ease itself into your spare tabs, onto your phone and behind your eyelids. It is the world you can escape to while queuing for coffee and when clicking away from the horrors of social media. It can provide, for you, regular smatterings of whimsy, awe and delight—if only you’ll let yourself fall in.

Read the full article here