In the summer of 1984, Paul Brainerd and four engineers packed into his old Saab and drove south on Interstate 5 from the Seattle area. They had been laid off after Kodak bought their employer, Atex, a company whose computerized text-processing systems let newspaper reporters and editors write and edit stories on video terminals instead of typewriters.

They had six months of savings, a rough idea for a piece of software, and no company name.

They stopped in towns along the way, pitching small newspapers and magazine publishers on a page-layout tool for desktop computers. The response was discouraging. The chains that were already buying up many of the publications took years to make purchasing decisions. A startup with six months of runway would be dead long before the first purchase order arrived.

They needed a new plan. They also needed a name: incorporation papers were due in a week.

What happened next was documented years later in oral history interviews with Brainerd for the Computer History Museum, and Seattle’s Museum of History and Industry.

They stopped at the Oregon State University library in Corvallis, rented a room, and started digging into books on the history of publishing. Brainerd found a chapter on Aldus Manutius, a 15th-century Venetian printer who had standardized typefaces, invented the small-book format, and brought the cost of publishing down far enough to reach ordinary people.

It was the perfect name for the revolution he had in mind.

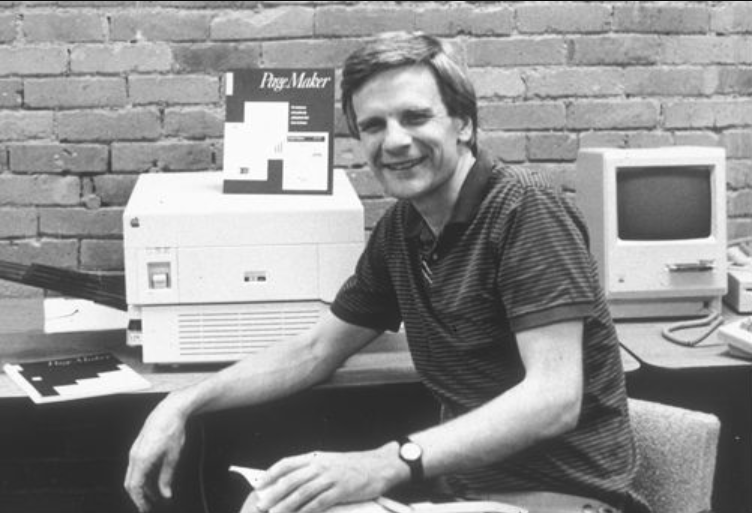

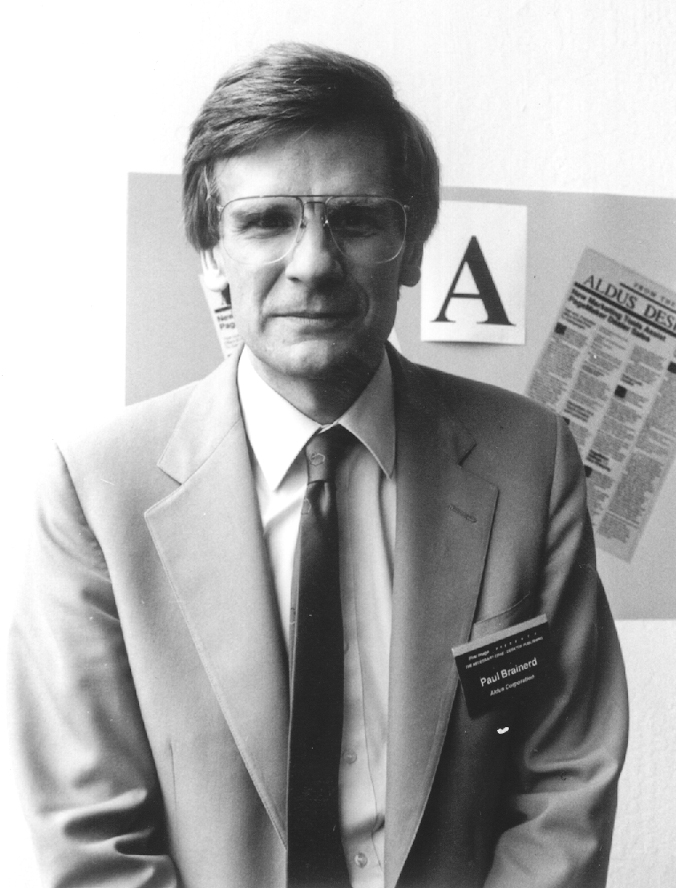

Paul Brainerd, who went on to coin the term “desktop publishing” and build Aldus Corporation’s PageMaker into one of the defining programs of the personal computer era, died Sunday at his home on Bainbridge Island, Wash., after living for many years with Parkinson’s disease. He was 78 years old.

He left two legacies. The first was a piece of software that put the power of the printed page into the hands of millions of people who had never operated a typesetting machine. The second was a three-decade commitment to environmental conservation and philanthropy in the Pacific Northwest, pursuing it with the same intensity he brought to the desktop publishing revolution.

Friends and colleagues this week remembered Brainerd as a quiet, caring and detail-oriented leader with exacting standards. He insisted that PageMaker use proper curly quotation marks instead of straight ones, and obsessed over nuances such as kerning, the precise spacing between specific letter pairs.

“Everything he did, he did with integrity,” said Laura Urban Perry, who was art director of Seattle Weekly when she spotted an ad in the back of the paper, answered it, and became Aldus’ seventh employee in 1984 when it was based in a small office near the Pioneer Square pergola.

Brainerd sat her next to the engineers so design and development would be in constant conversation. In essence, she was working in user experience before the term was widely used. They gave her the desk by the window, she said, because artists need light.

Ben Rotholtz, who had worked at a Seattle art supply store selling press-on lettering to graphic designers, went to Aldus on Christmas Eve 1985 to apply for a tech support job. He laid out a page on an Apple Macintosh and watched it come out of an Apple LaserWriter exactly as it appeared on screen. (“My jaw just dropped,” he said.)

Rotholtz started at the company in January 1986. Many of the customers needing support had never owned a computer before. PageMaker was often the reason they bought one.

Before shipping PageMaker 3.0, Brainerd told Rotholtz that every department had signed off on the release except his. If tech support said it wasn’t ready, they wouldn’t ship. “Customer support was basically another feature in the product,” Rotholtz said. “He valued it that highly.”

Brainerd applied the same evenhanded principles to business partnerships. When Rotholtz proved to be an effective negotiator on technology licensing deals, Brainerd told him not to “over-negotiate” — to make sure the other side could survive and thrive, too.

That focus on customers is what revealed the true market for PageMaker. Brainerd and his team had expected to sell to professional graphic designers and newspaper publishers. Instead, the calls came from churches, colleges, nonprofits, and small businesses.

Brainerd loved to tell the story of a pastor from the Midwest who called to say he was using PageMaker to print 600,000 religious pamphlets. Or the mother in San Francisco who wrote to say she had used PageMaker to design and print a picture book for her children. It might seem trivial today, but back then it otherwise would have required a professional printer.

Telling those stories to the public was a core part of the company’s strategy, said Laury Bryant, who worked at Aldus from 1987 to 1991 as a PR and investor relations leader. “Every day, there was some new and incredible way the product was being used,” she said.

To Rotholtz, the product had a clear and profound impact on the world: “PageMaker was ultimately about the democratization of printing and publishing.”

Brainerd had lived the journey that made it possible.

From letterpress to laser printer

He was born in 1947 in Medford, Ore., a small town in the Rogue Valley with an economy dependent on pears and lumber. His parents, Phil and VerNetta Brainerd, ran a photography studio and camera shop on Main Street. He grew up in darkrooms in the family business.

He was a B+ student, more interested in the yearbook than the classroom. When he got to the University of Oregon, he majored in business but spent all his time in the journalism school. He became editor-in-chief of the Oregon Daily Emerald in his senior year.

Along the way, he converted the campus newspaper from letterpress, a centuries-old method of pressing inked metal type onto paper, to offset printing, a faster and cheaper photographic process. He did the same thing later at the University of Minnesota student paper.

It would become a recurring theme: moving from one era of publishing to the next.

After getting his master’s in journalism from the University of Minnesota, he went to the Minneapolis Star Tribune as assistant operations director, overseeing a transition from hot type, in which molten lead was cast into lines of text, to cold type, which used light and film instead.

It was at the Star Tribune that Brainerd had a realization that defined his career. He was sitting in the office of Charles Bailey, the paper’s editor-in-chief, listening to Bailey discuss the day’s political coverage. “I just realized, in that moment, that I was never going to be a Charles Bailey,” Brainerd later recalled. “I could be a lot of other things, but I was never going to be him.”

But he could translate between the people who built technology and the people who used it.

He joined Atex, one of the Star Tribune’s vendors, and eventually moved to Redmond to run the company’s West Coast R&D arm. When Kodak bought Atex and shut the plant down, Brainerd was 37 and out of work. He had about $100,000 in savings. He decided it was now or never.

Brainerd put up his own money to start Aldus. The engineers who joined him from Atex worked at half salary. He took no salary at all. They gave themselves six months to write a business plan, build a prototype, and find funding.

He called 50 venture capital firms. Forty-nine said no. In 1984, most investors saw no value in software companies. Microsoft had not yet gone public. The prevailing view was that software could be replicated in a weekend by a couple of guys in a garage.

With about $5,000 left in the bank, a firm called Vanguard Ventures in Palo Alto said yes. Some of its general partners were former Apple executives who understood what software could do. They invested $864,000. A small local firm, Fluke Management Capital, also took a position.

Sparking a revolution

Their product was PageMaker, a program that let anyone lay out text and graphics on a computer screen and send it to a printer. Brainerd and his team realized that three things had to come together to make it work: Apple’s Macintosh, which provided the graphical interface; Adobe’s PostScript, which gave printers the ability to render high-quality type and images; and a piece of software that tied them together. Brainerd called it the “three-legged stool.”

At a board meeting in late 1984, an investor told them they needed to boil down their wordy description of what they were doing — putting text and graphics on pages — to two words, as Brainerd recalled in his 2006 oral history with the Computer History Museum.

Someone suggested “desktop something.”

Brainerd said, “How about desktop publishing?”

Back at the office, the engineers were skeptical, but Brainerd went with it, and it stuck.

PageMaker 1.0 shipped in July 1985. It gave Apple a reason to exist in the corporate market. Steve Jobs later said that desktop publishing had saved the Macintosh.

PageMaker shipped on Windows in 1987, before Microsoft Word did. The Microsoft program manager who convinced Aldus to build on Windows was Gabe Newell, who later founded Valve. Bill Gates and Steve Ballmer sent a bottle of Dom Perignon to celebrate the launch.

In 1991, Soviet hardliners attempted a coup in Moscow. They locked down the traditional printing presses to control the flow of information. But they couldn’t hold back computers. Across the city, pro-democracy activists used PageMaker to produce and distribute handouts. Aldus later ran an ad about it, with the tagline: “We helped create a revolution.”

Aldus co-founder and engineering lead Jeremy Jaech, who had been one of the engineers on that fateful 1984 road trip — along with Mark Sundstrom, Mike Templeman, and Dave Walter — said Brainerd set a high bar for the people around him.

“He wasn’t a yeller,” Jaech said. “He would talk to you in a low voice and tell you all the things you were doing wrong.” But Jaech said Brainerd got the best out of people. “I worked my ass off for him because I wanted to please him — and he was hard to please.”

Jaech, who went on to co-found Visio, the diagramming software company that Microsoft later acquired for $1.5 billion, said he wouldn’t have been prepared to start his own company without everything he learned from Brainerd.

“Product focus, customer focus, how to build a board, how to run a meeting,” Jaech said, running down the list. “There’s no question I got a lot.”

He wasn’t the only one. Bill McAleer, who joined Aldus as chief financial officer in 1988, said more entrepreneurs came out of Aldus, proportionally, than out of Microsoft at the time. Brainerd “created a great culture,” simultaneously entrepreneurial and collaborative, said McAleer, who went on to co-found the venture capital firm Voyager Capital.

The bonds among Aldus employees have lasted to this day, said Perry, the former Aldus art director who remained in touch with Brainerd over the years, interviewing him on video for a 2022 conference talk she gave about the desktop publishing revolution.

But after a decade at the helm, Brainerd was worn out. “It was my child, basically,” he said in his 2009 oral history, recorded at KCTS Television for MOHAI’s Speaking of Seattle: Experienced Leaders Project. “After 10 years of doing that, I was ready to let it go.”

He found his exit in the 1994 merger of Aldus with Adobe, the company whose PostScript technology had been one of the three legs of the desktop publishing stool from the start.

By then, PageMaker faced stiff competition from QuarkXPress, which had captured a large portion of the professional design market. PageMaker’s strength — its broad appeal to everyone from churches to corporations — had become a strategic vulnerability.

Years after the acquisition, Aldus would end up forming the nucleus of Adobe’s campus in Seattle’s Fremont neighborhood. PageMaker’s desktop publishing legacy lives on in the program known today as Adobe InDesign, built from the ground up to win back the professionals.

McAleer, who oversaw the deal for Aldus and ran the subsequent integration, said it was a natural fit: “When we merged the two companies, that really created a very broad-based graphics suite for graphics professionals and people in the publishing industry.”

The all-stock deal, valued at roughly $525 million at the time it was announced, closed in August 1994. Brainerd was Adobe’s largest individual shareholder, with stock worth roughly $100 million. He served on Adobe’s board for two years but never returned to management.

Perry wasn’t surprised by Brainerd’s shift in focus. “He just figured out what was important to do next and got after it,” she said. “It wasn’t about making money and becoming a billionaire.”

‘If I gave you the checkbook …‘

Brainerd took six weeks off and went to Alaska to hike and clear his head. Then he took a third of his proceeds from the Adobe deal and created the Brainerd Foundation.

He spent three months driving around the Pacific Northwest, talking to roughly a hundred people and asking a single question: If I gave you the checkbook, who would you write it to? The foundation focused on environmental conservation across Oregon, Washington, Idaho, Montana, British Columbia, and Alaska.

In 1997, Brainerd and fellow Seattle business leaders Scott Oki, Ida Cole, Bill Neukom, and Doug and Maggie Walker co-founded Social Venture Partners, which applied the venture capital model to philanthropy, as detailed in a 2018 GeekWire profile. Partners pooled their money, researched community needs, and invested in nonprofit organizations.

In 2000, Paul and Debbi Brainerd founded IslandWood, a children’s environmental learning center on 256 acres they purchased and donated on Bainbridge Island. About 3,000 students a year visit the campus to learn about watersheds, water quality, and forest ecology.

Paul and Debbi Brainerd did not have children, and he was clear about the fact that his goal was to give his money away. “He wasn’t going to take it with him,” said Bryant, the former Aldus PR and investor relations manager who later served on the IslandWood board.

In later years, the Brainerds built Camp Glenorchy, a net-zero eco-lodge near Queenstown, New Zealand, and spent about half of each year there. They revitalized the town’s struggling general store, helped bring internet access to the community, and donated proceeds to local causes.

Brainerd “personified the best of an era when tech innovators not only took smart ideas to scale but shared a broad vision of how to make the world a better place — and got to work to make it happen,” said Leonard Garfield, executive director of the Museum of History and Industry.

Ted Johnson, a programmer who had worked with Brainerd at the Star Tribune, Atex, and Aldus, visited Glenorchy with his wife and watched Brainerd show off the composting systems and water treatment infrastructure with all the enthusiasm he once gave to kerning and quote marks.

“He loved nature,” Johnson said, “and he loved technology.”

Brainerd is survived by his sister, Sherry, and his wife, Debbi, who described his more than 20-year battle with Parkinson’s disease in a letter to his friends and colleagues this week.

“I have never seen anyone fight so hard and for so long, looking for traditional medical treatments, as well as non-traditional healing practices that could help him manage the growing number of symptoms that his Parkinson’s presented,” she wrote.

He ultimately chose to take advantage of Washington state’s Death with Dignity Act, “allowing him to choose his time and place of passing,” she wrote. “He died peacefully on Sunday, viewing the Puget Sound landscape he loved, outside our home on Bainbridge Island.”

Family and friends are planning a celebration of life at IslandWood in June. Memorial donations in Paul Brainerd’s honor can be made to IslandWood at islandwood.org.

Reporting for this story included interviews with Brainerd’s former Aldus colleagues Ben Rotholtz, Laura Urban Perry, Laury Bryant, Jeremy Jaech, Bill McAleer, and Ted Johnson, coordinated with the help of Pam Miller, a former Aldus employee; oral history interviews with Brainerd conducted for the Computer History Museum (2006) and Museum of History and Industry (2009); a video interview with Brainerd conducted by Perry in 2022; and a 2018 profile by GeekWire reporter Lisa Stiffler.

Read the full article here